Tips

Comfort and Biases

Some people have little desire to understand the world as it actually is through reason and science. Instead, they live within comforting belief frameworks that are disconnected from reality but make life feel manageable in a chaotic world. These frameworks persist not because they are accurate, but because they provide psychological stability and a sense of certainty. While it can be tempting to dismiss this as intellectual emptiness, the pattern is better understood as a well-documented set of cognitive and social mechanisms rather than a simple personal failing.

What Is Happening, in Concrete Terms

1. Motivated Cognition

Many people do not treat beliefs as models of reality but as tools for emotional regulation and social belonging. Accuracy is secondary to psychological comfort, identity preservation, and group cohesion. Reasoning becomes instrumental rather than truth-seeking, with evidence filtered according to whether it threatens internal equilibrium or social standing.

2. Cognitive Economy and Load Avoidance

Deep understanding is costly. It requires sustained attention, tolerance for ambiguity, and a willingness to revise one’s worldview. Most people optimize for cognitive efficiency rather than correctness, adopting prefabricated explanatory frameworks—ideological, religious, cultural, or conspiratorial—that minimize cognitive effort while still providing narrative coherence. This is not stupidity; it is energy conservation.

3. Epistemic Closure

Once a framework is adopted, individuals often seal themselves inside it through selective exposure, distrust of external authorities, and circular justification. Within such closed systems, beliefs appear internally coherent even when misaligned with external reality. From the inside, there is no obvious exit.

4. Low Epistemic Curiosity

Some individuals lack intrinsic motivation to ask foundational “why” questions beyond what is functionally necessary for daily life. Their curiosity is practical rather than explanatory. They are not trying to understand the world in general; they are trying to navigate their own immediate environment.

5. Fear of Existential Destabilization

Abandoning a worldview can imply loss of meaning, identity, and community. The persistence of the “cave” is often driven less by ignorance than by fear—leaving feels like psychological annihilation.

Why These Frameworks Persist

Such belief systems reduce anxiety, provide certainty in chaos, externalize blame, and offer moral simplicity. From an evolutionary and social standpoint, these traits are adaptive even when epistemically false. Truth is not evolution’s priority; stability often is.

Language for Describing the Phenomenon

The following terms describe belief patterns that prioritize comfort and stability over accuracy, focusing on epistemic dynamics rather than personal judgment:

- Epistemically Insulated — Emphasizes resistance to external correction.

- Cognitively Outsourced — Highlights reliance on pre-packaged narratives.

- Narrative-Dependent — Distinguishes stories from reality-tracking models.

- Psychologically Stabilized Belief Holders — Describes functional purpose rather than deficiency.

- Low Epistemic Agency — Indicates limited initiative to independently evaluate beliefs.

- Framework-Bound — Neutral and broadly applicable.

- Cognitively Uncurious — Indicates limited drive to investigate underlying causes.

A Difficult but Important Observation

Individuals who actively pursue reality through reason and science are a minority — not due to incapacity, but because truth-seeking is psychologically disruptive and socially costly. The tension often arises from differing epistemic goals: one side seeks beliefs that track reality; the other seeks beliefs that preserve equilibrium. Recognizing this distinction makes the phenomenon less baffling and more predictable.

The Ultimate Bias

One final point is worth emphasizing: none of the patterns described above apply only to other people. Human thinking is shaped by bias across the board, and failing to notice this is itself a serious mistake.

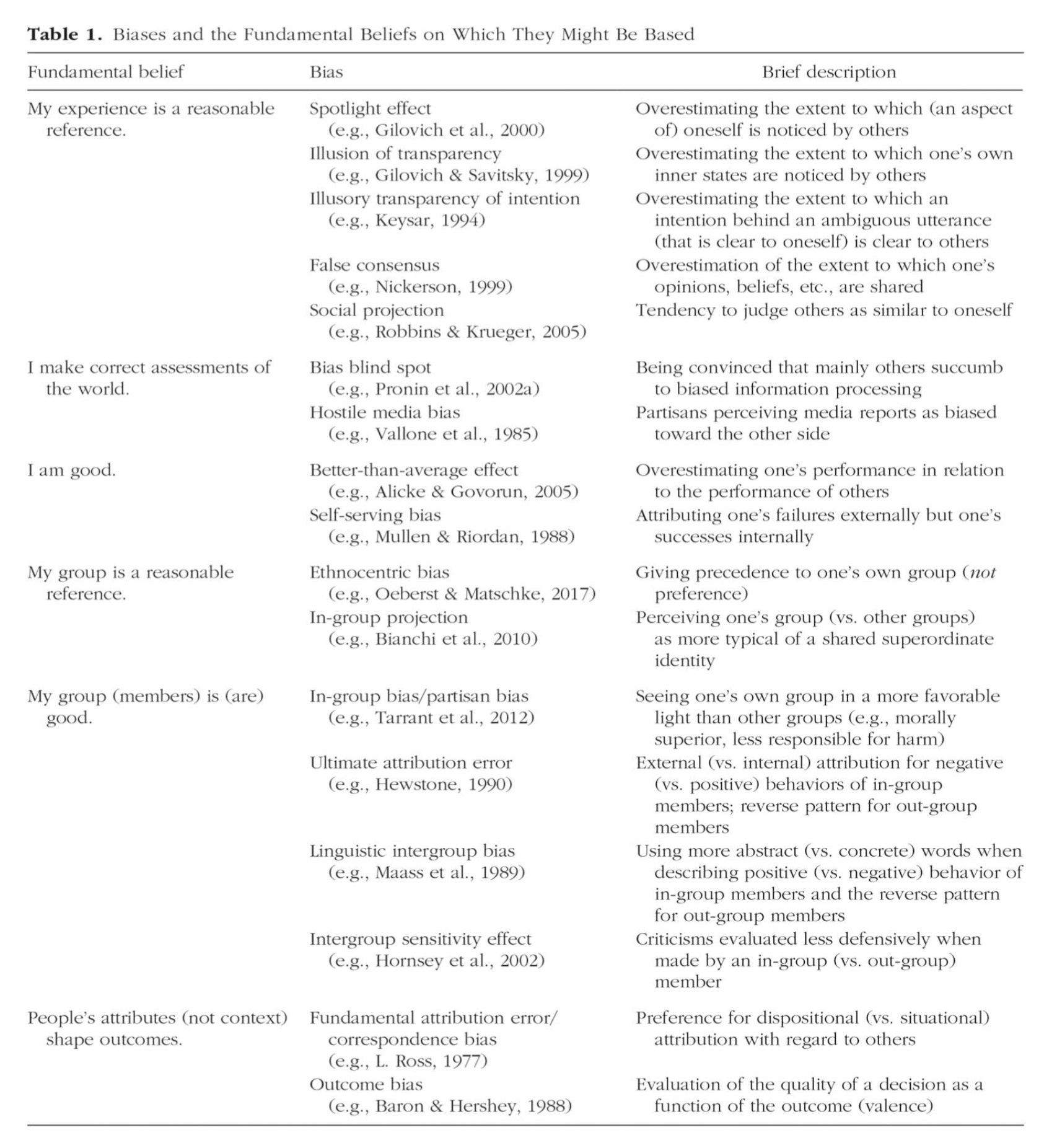

Research discussed by Steve Stewart-Williams suggests that many familiar cognitive biases may stem from a small set of core beliefs rather than dozens of separate flaws. A paper by Aileen Oeberst and Roland Imhoff argues that most biases arise from a few basic assumptions, such as “I make accurate judgments” or “I am a good and capable person.” These beliefs are then reinforced by a single, overarching tendency:

“…all our cognitive biases boil down to one of a handful of fundamental beliefs, coupled with one ultimate bias.”

That ultimate bias is confirmation bias — the tendency to seek out and favor information that supports what we already believe. It reflects the reflexivity limitation: our brains cannot fully monitor their own reasoning, so we naturally favor beliefs we already hold. Once a belief provides comfort, identity, or stability, we naturally pay more attention to evidence that supports it and downplay evidence that challenges it. Over time, this creates the illusion that the belief is well-supported, even when it is not, quietly sustaining many of the dynamics discussed earlier.

Table 1 below illustrates how common cognitive biases may be rooted in these deeper self-protective beliefs:

Source: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/17456916221148147

The takeaway is simple but uncomfortable: the same forces that keep others locked into comforting worldviews are at work in all of us. The real difference lies not in being free of bias, but in whether we are willing to notice it and correct for it.

Conclusion: Practicing Epistemic Humility

Recognizing that bias is universal is only the first step. The key is cultivating epistemic humility — the willingness to question your own beliefs and remain open to evidence, even when it challenges comfort or identity.

Some practical habits include:

- Pause and reflect - Before fully accepting information, ask why you believe it and whether it might be influenced by prior assumptions.

- Seek diverse perspectives - Engage with sources and people who think differently, not to argue, but to understand.

- Test your beliefs - Look for credible evidence that could disprove what you hold to be true.

- Separate comfort from truth - Notice when a belief feels good or reassuring, and ask whether that feeling is influencing your judgment.

These practices do not eliminate bias, but they help prevent it from silently guiding your thinking. Over time, small acts of vigilance strengthen the ability to see the world more accurately, even in the face of uncertainty and discomfort.

A cautionary note: Even with these habits, there are limits. Successfully questioning your own beliefs depends on reflexivity — the ability to step outside your own thinking and notice assumptions. Not everyone has this capacity to the same degree, and it cannot be fully “switched on.” Without sufficient reflexivity, reasoning can easily drift into rationalization, and first impressions may feel like facts.

For practical ways to extend your reflexivity beyond its natural limits, see Augmenting Reflexivity. These external scaffolds — social feedback, accountability systems, diverse inputs, AI tools, and environmental design — can complement your internal reflection, helping contain bias and gradually strengthen awareness over time.

The goal is not perfection but sustained effort: to contain bias where possible and continuously improve your capacity for self-monitoring and critical thought.